Iran’s “Liberty or Death” Moment

Whether from weariness over decades of Middle Eastern conflict, financial concerns at home, or an isolationist sense of "this isn't our fight," Americans are not nearly as invested in the outcome of the current Iranian Revolution (not to be confused with the 1979 Islamic coup) as this movement deserves. Even if there exists an unfortunate ambivalence toward Iranians winning freedom for their own right, Iranians are facing a point of no return with striking resemblance to the birth of the United States. We should be cheering for them.

We are witnessing Iran’s own “give me liberty, or give me death” moment. After 47 years of abject horror and brutality under an Islamic Republic with no regard for its own people, Iranians have finally reached the point where their desire for freedom outweighs their fear of the regime. The most devastating threat to the mullahs is not foreign military intervention (though, to be clear, The Free Iran Project strongly advocates for this); it’s the Iranians’ irreversible fearlessness.

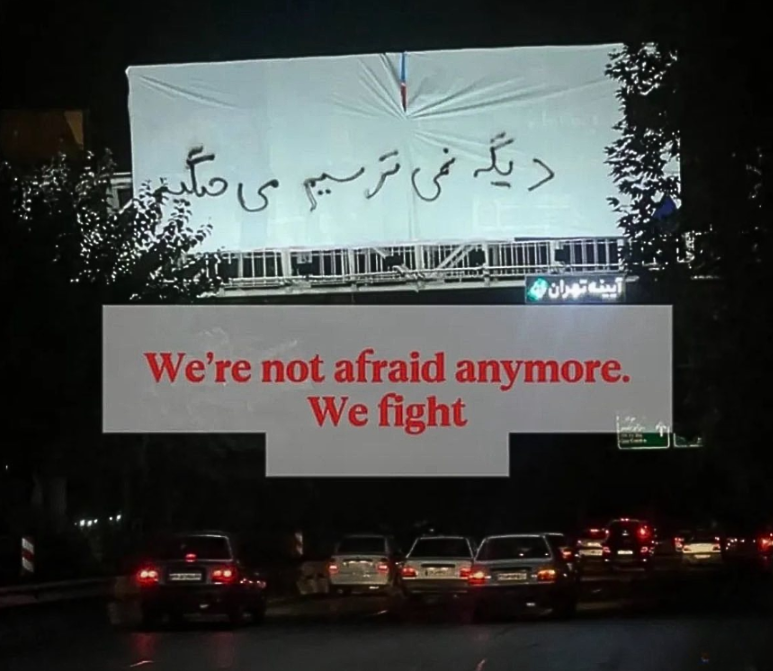

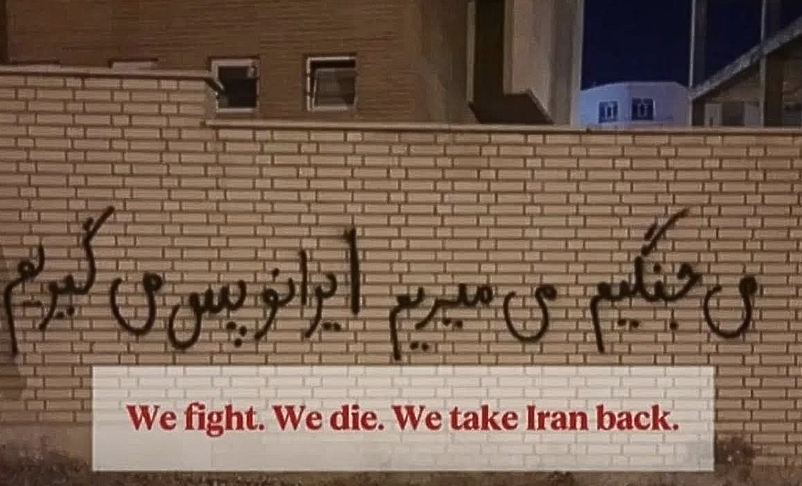

“We’re not afraid anymore. We fight.”

Sign on overpass in Iran with overlaid translation.

Mirrored Turning Points: 1775 and 2026

Borrowing famous lines from history can sound like a meme: consumable, quickly satisfying, and vague enough to use for any struggle that looks heroic. But the power of “give me liberty or give me death,” and its parallel to Iran, comes from a very precise turning point: the moment when a population begins to speak and act as though there is no further room for debate. Every detail may not be settled, but they have crossed the moral threshold of accepting the risk. Just like the Americans in 1775, Iranians understand that the petitions, patience, and accepting the regime's laughably superfluous concessions after previous uprisings amount to no more than surrender.

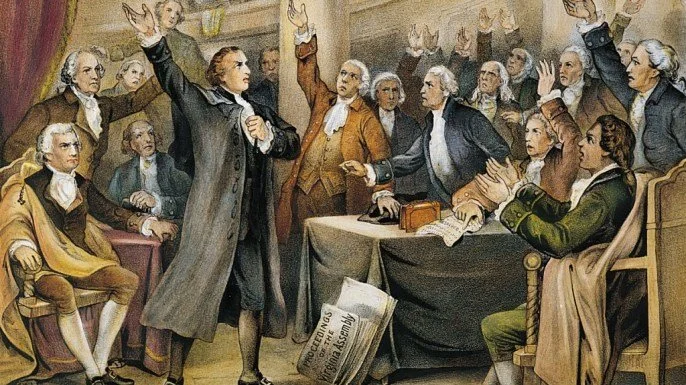

Artist rendition of Patrick Henry giving his famous, galvanizing speech in 1775, Virgina

Iran is not reenacting 1775, of course; aside from very different histories and cultures, Iranians are objectively under a great deal more oppression than the American colonies ever faced. However, both moments are a function of the same political mechanism: when a ruling system becomes illegitimate, it can use coercion to silence people, but it can’t re-create belief.

What Did This Speech Actually Signal?

The famous line is attributed to Patrick Henry in his speech to the Second Virginia Convention in March 1775. Virginia’s political leadership was confronting dissolutions of colonial assemblies, intense coercion, and the realization that “more negotiation” was just a delay tactic (sound familiar?) while imperial controls tightened around them. Henry’s speech was really a push to move beyond protest and prepare for conflict, and to abandon the fantasy that a few more rounds of pleading would restore the liberties they’d already lost.

It also matters that there is no verbatim transcript of Henry’s speech, and the most widely circulated version was reconstructed decades later. This does not weaken its relevance, but strengthens it if we use it correctly.

The beauty of “give me liberty, or give me death” is that it reduces the political argument into an ethical binary: not “would you like more freedom,” but “is life worth living without freedom?” This forces us to stop shielding a historic moment in ambiguity. With the binary, we must pick a side and accept the consequences of choosing. In that context, “liberty or death” is a population stepping off a precipice, because the cost of staying on the cliff is higher than jumping into the void below.

In the Iran parallel we are not claiming the same sequence of events, actors, or institutions. We argue that Iranians are at a similar threshold of moral clarity, where reform is delay and the path toward freedom leaves no room for compromise.

When Fear Stops Working

The Islamic Republic has always relied on a twisted, fear-based version of the social contract to stay in power: comply, keep your head down, and you may be allowed a life. A constrained, surveilled, and spiritually policed life, but maybe you’ll live to old age and not spend most of it in a political prison. The function of the IRGC is to enforce this system, brutally, which is why many Iranians hate them even more than Khamenei.

When this social bargaining collapses, authoritarian regimes do not immediately fall, but they do typically grow more violent. They are an animal backed into a corner. But the collapse changes something irreversibly: people stop acting as if the system that cares nothing for its people can be bargained with.

We’ve seen this in the past month with the massive, nationwide protests in Iran, the staggeringly violent IRGC crackdowns amid an information blackout, and then the regime’s declaration that they’d restored normality (which would be amusing if it weren’t both horrific and false). But unlike the Green Movement in 2009, Bloody November in 2019, and Mahsa Amini (Women, Life, Freedom) uprising in 2022 that were suppressed and reverted to more or less the status quo, the repression and brutality against the current revolution are unintentionally persuading more citizens that there is no going back.

“We are past the point of just wanting to be free; we want to see them bleed. The IRGC started this, and we will finish it and get rid of this cancer. There is no going back, because the way back is filled with blood.”

This is also why we should read the regime’s obsession with narrative control (internet blackouts, censorship, forced confessions, propaganda) as a sign of brittleness. It is the behavior of a regime trying to rebuild fear because belief is entirely gone.

The recurring theme among Iran coverage now is that the Islamic Republic’s options are narrowing, and while they respond with force and emergency measures, the people have only become more angry and determined. A state cannot easily regain legitimacy once the majority of its citizens no longer take it seriously.

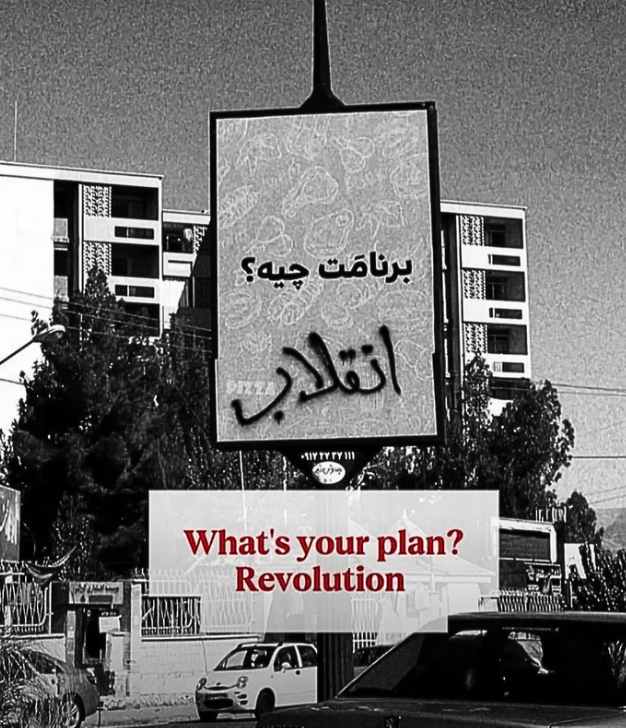

Graffiti reply of “Revolution” to advertising billboard asking, “What’s your plan?”

Why Revolutions Speak in Absolutes

Revolutions speak in absolutes because they do not begin in hope or optimism, but in refusal. When a population concludes that the system ruling it is unreformable, that further debate only entrenches abuse, and that moral clarity is no longer optional but necessary for survival.

Absolutes do three things at once.

They convert private suffering into public purpose. Millions of isolated humiliations - homes raided, dehumanizing interrogation and torture tactics, or forced confessions on television - become a shared story.

They untangle complexity into the ethical binary we discussed earlier. This is not because revolutionaries are naïve, but because the regime will often use complexity and subterfuge as a trap to delay, strengthen, and oppress: “There are pros and cons,” “it’s not that simple,” “don’t destabilize.” Absolutist language sidesteps the trap. It says: the foundational issue is not complicated. Human beings are not property of the regime.

It creates a test for outsiders: Where do you stand when neutrality is complicity? The test is aimed not only at domestic fence-sitters, but also at the comfortable, distant Western observers whose complacence leads them to interpret Iran as a tragic, endless regional story rather than a live contest over human agency by a people fighting for the same rights they themselves enjoy.

This is one area where diaspora voices can help the most. Not as stand-ins for Iranians inside the country, but as a way to translate urgency to audiences that default to fatigue amidst a blithely indifferent news cycle.

Four Parallels Worth Taking Seriously

Iran’s “liberty or death” moment in a nutshell. Aside from videos of protesters shouting, verbatim, “I will die for a free Iran,” “We will be free or die,” there are other parallels that should catch the American ear.

Legitimacy crisis. In both the American Revolution and Iran today, the people generally stopped believing the ruling power can be reasoned with. They realized the regime is fundamentally incapable of responding to rational argument, and begin treating it as the enemy. That shift is dramatic in Iranian unrest. It’s not a narrow, one-issue protest with specific demands (economic woes, etc.), but as a challenge to the regime’s right to rule.

Repression as accelerant. Coercion can suppress demonstrations, but it also highlights the moral stakes. Every murder, arrest, forced confession, or blackout is a message: the regime knows it cannot win a fair contest..

Information networks. The American revolutionaries had committees, pamphlets, and meeting houses. Today’s dissidents have encrypted channels, diaspora media, and viral testimony, and the IRGC responded with digital suffocation because information is oxygen.

The “after” question. Revolutions become real when they can speak in future tense. The future doesn’t have to be perfectly mapped in advance, but people will not risk everything for an empty abstraction, especially if there’s danger of a power vacuum. They need a credible picture of what comes after the revolution, even if it is transitional..

The Limits of Comparison

A Revolution in the 1700s in North America and one in the Middle East in the digital age are certainly not going to dovetail completely.

First, the American Revolution was a colonial fracture, while Iran’s struggle is internal regime change. The institutional terrain is very different. Colonial assemblies and elites had footholds that dissidents inside Iran cannot easily maintain under surveillance and mass imprisonment.

Second, geopolitics surrounds Iran’s context in a way 1775 Virginia did not face at the same scale. Regional conflict, proxy dynamics, sanctions framework, and global energy and security calculations all shape possibilities and incentives.

Third, the risk is categorically different. Those participating in anti-British activities pre-1775 did so at great personal risk, but in Iran’s modern landscape of digital tracking, forced confessions, almost guaranteed torture, and often execution, Iranians’ fear of physical harm is almost certainly higher.

These differences matter because they change timelines and tactics. But they don’t erase the core parallel: when a regime is deemed unreformable by the people living under it, removing it becomes the only option.

Speaking to the West: Clarity, Controversy, and the Price of Attention

Iran commentators and diaspora members often sound “too certain” to Western audiences trained to distrust a binary. But what breaks through ambivalence more than certainty? If any issue has been overcomplicated by endless political discourse and dissection, it’s Iran. It truly is as simple as supporting either the Islamic Republic, or supporting the people. There can be no freedom for the people while the Islamic Republic exists.

Goldie Ghamari is one example of a diaspora political figure who’s built her public persona around confronting the Islamic Republic and advocating for hard lines that Western institutions often avoid. That she’s a former member of Ontario’s legislature gives her a different kind of legitimacy in Western discourse - she can speak in the language of policy, law, and public institutions, not only personal testimony.

When reading about Iran, it’s critical to look for voices that:

Only entertain regime change, not reform; reform is a Islamic Republic talking point, repeated ad nauseum

Have contact with friends, family, and associates inside Iran in the opposition.

Support a centralized transitional leadership. Right now, this is Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi. Even for those who typically don’t believe in monarchy, if the Iranian people chose him, he represents the quickest, cleanest path toward a peaceful transition of power when the regime falls.

A Revolution Needs a Future Tense

In January 2026, Reza Pahlavi framed the moment as a national revolution and positioned the Islamic Republic as an occupying force rather than a legitimate government. This was a brilliant way to shape public perception and discourse, and helps to further delegitimize the regime.

When Western governments discussed regime change in the past, a frequent hesitancy was the possibility of a power vacuum similar to that in many of the Arab countries whose leaders fell during the Arab Spring. What they fail, repeatedly, to understand, is that Iran is not a country that was created by foreign powers in the last century around historically warring disparate factions, with arbitrary borders. Persians have over 3000 years of history binding them to the land and to each other, which is what’s protected them from Islamization despite being under theocratic rule. This deep cultural pride, plus a central, recognizable, and galvanizing figure in Reza Pahlavi, makes the risk of a power vacuum significantly less likely.

Also unlike the Arab Spring, the aim of the Iranian revolution is not simply the removal of their oppressors. The overarching goal is a bright future they can never have under the current theocracy, and getting rid of the mullahs is the means to that end. Iranians have imagined and planned for this better future for nearly fifty years.

Liberty Isn’t a Slogan

The word “liberty” meant something specific to the American revolutionaries: representation, consent, and the right not to be governed by decrees from across the world. In Iran’s revolution, liberty is arguably more intimate and more total: bodily autonomy, freedom of belief, freedom from ideological policing, and the right to live without being collateral damage from the government’s totalitarian ambitions.

But the soul of the idea is the same. Liberty, in both contexts, is simply that a human being is not the property of the state. This is why “liberty or death” resonates even with its imperfect historical record. It names the exact point when a group of people decide that survival without dignity is not survival.

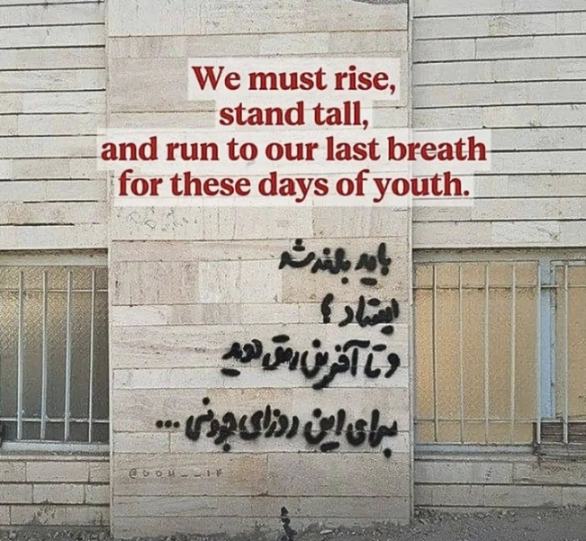

“We must rise, stand tall, and run to our last breath for these days of youth.”

We Didn’t Do it Alone

Although Americans fought the lion’s share of the Revolution themselves, they did not do it alone. Foreign recognition, material support, and strategic pressure on the British Empire significantly helped tip the scales - not because others won the war for them, but because intervention made freedom possible at a decisive moment. Why should Iran’s revolution be any different? They are sacrificing their lives in the name of freedom; do they not merit help?

Iranians are doing the most dangerous work themselves, at astronomical cost. What they need from the West is not hand-wringing, neutrality, or calls for restraint, but moral clarity and decisive action that matches the stakes. History does not judge these moments by how cautiously foreign powers hedged, but by whether they stood with the people who had already accepted the risk. When a nation reaches its liberty-or-death moment, the only unforgivable choice is pretending it isn’t happening.

What We Owe the People Who Take the Risk

My fellow Americans, please don't demand that that the Iranians’ struggle fit our preferences: nonviolent but effective, principled but strategically perfect, heroic but not destabilizing, inspiring but not morally demanding. It’s not our place to lecture them on their methods or encourage restraint.

What we should give Iranians is recognition that they are fighting for the same fundamental rights Americans consider universal, and that they are doing so under brutality most of us will never experience. We owe them acknowledgement that the Islamic Republic is not a legitimate government in conflict with its people, but an occupying regime holding an ancient nation hostage.

Neutrality in this revolution is abdication, not diplomacy. The Iranian people have already crossed the line where fear no longer governs their behavior, so outsiders should not pretend the moral question remains unsettled. History does not remember who urged caution, and in this case, urging caution is akin to condemning Iranians to death. It remembers who recognized the tipping for what it was, and chose to stand on the right side of it.

Iranians are in their “liberty or death moment,” and we cannot look away.

“We fight. We die. We take Iran back.”

==========

Natalia Butler (nom de guerre) works in marketing, but her vocation is Iran. Passionate about the loving, deeply-alive nature of Iranians even in the face of decades of oppression. She has dedicated much of her time to studying Iran and has worked with opposition groups to help write legislation proposals, lobby for sanctions against the regime, etc. Natalia looks forward to writing articles from a cafe in Tehran very, very soon.